Neanderthals’ intelligence and toolmaking skills revealed by modern technology

In a new paper published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, researchers from the University of Wollongong in Australia have discovered that Neanderthals had precise control over the angle at which they struck stone cores to produce tools, offering new information on the cognitive and motor skills involved in Middle Paleolithic stone tool production.

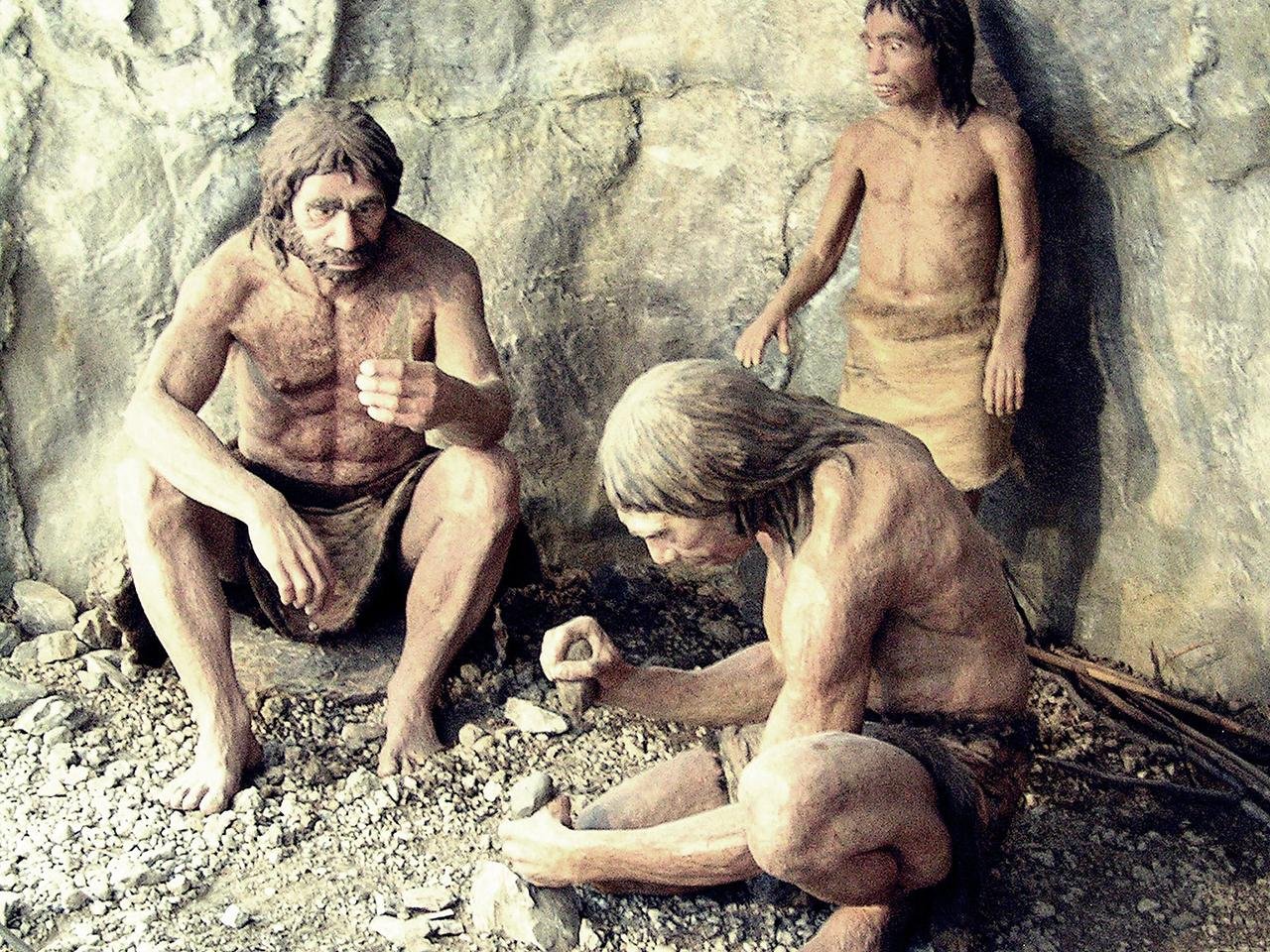

The team conducted a series of controlled experiments where they tested the effect of variation in the angle of hammer strikes—referred to as the angle of blow (AOB)—on the morphology of stone flakes produced by the Levallois technique. This method, employed by Neanderthals between 200,000 and 400,000 years ago in Africa, Europe, and Asia, involves preparing a stone core in such a way that it is possible to remove flakes of predetermined size and shape. Although once considered to be an indicator of advanced planning, the Levallois method has been linked to complex behaviors such as foresight, long-term memory, and even linguistic abilities.

The prevailing theory up to this point held that flake morphology was, to a large extent, determined by the core’s stiffness and geometry, and that the way force was applied during the strike had very little influence. That presumption is directly challenged by this recent study.

To test this experimentally, the researchers created 20 experimental flakes from soda-lime glass cores, which were chosen for their consistency and fracture properties similar to natural flint. The cores were shaped with high accuracy by automated milling machines to match archaeological specimens. Controlled hammer blows were then delivered at three strike angles—0°, 10°, and 20°—through a pneumatic system and a custom 3D-printed mounting system.

3D scans and cross-sectional analysis revealed the same patterns: flakes produced with lower strike angles (closer to perpendicular) were significantly larger, thicker, and heavier, while those produced with more oblique blows were thinner and more pointed. Notably, the trajectory of the fracture also changed depending on the strike angle. At low angles, the crack propagated deeper and sliced through more of the core’s lateral and distal convexities, resulting in a larger flake.

These findings refute previous fracture models, which indicated that the stiffness of the forming flake would naturally self-correct the trajectory, restricting the impact of how force was applied. The research instead suggests that the angle of blow is a deliberate, skill-based variable that Neanderthal knappers adjusted to obtain desired results.

According to the researchers, detaching large flakes at low angles requires greater force and carries a higher risk of failure. This means that Levallois knappers would have to adjust and coordinate the angle of blow as part of the knapping gesture to successfully detach Levallois end products.

This more detailed understanding of flake production expands our appreciation of Neanderthal motor coordination and decision-making. Rather than being confined to preset patterns based on core shape, the fact that they could modify strike angles in the moment suggests a more dynamic, cognitively demanding toolmaking process.

The study not only reshapes long-standing presumptions about prehistoric technology but also reaffirms Neanderthal craftsmanship. Their mastery of the Levallois technique would have involved far more than geometry alone.